First Look at Reasoning From Scratch: Chapter 1

Subtitle: An introduction to reasoning in today’s LLMs

Date: JUL 19, 2025

URL: https://magazine.sebastianraschka.com/p/first-look-at-reasoning-from-scratch

Likes: LIKE (2)

Image Count: 7

Images

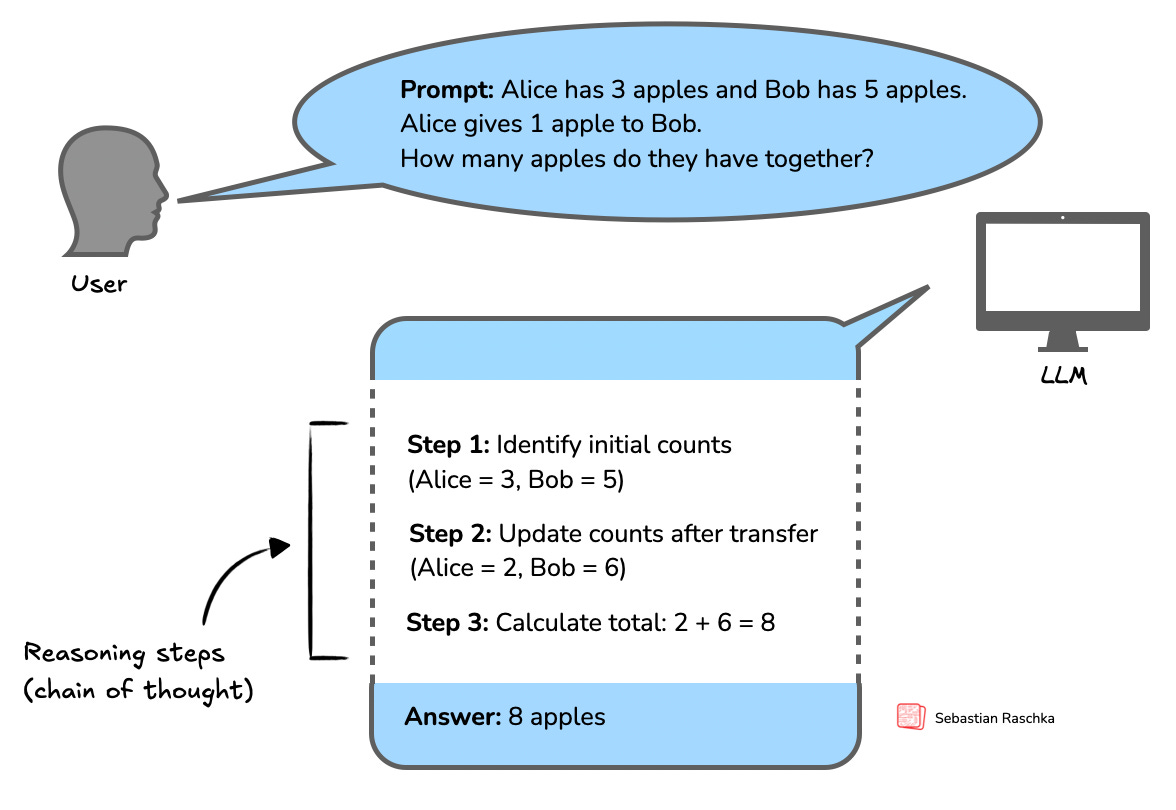

Figure - Caption: Figure 1.1: A simplified illustration of how an LLM might tackle a multi-step reasoning task. Rather than just recalling a fact, the model needs to combine several intermediate reasoning steps to arrive at the correct conclusion. The intermediate reasoning steps may or may not be shown to the user, depending on the implementation.

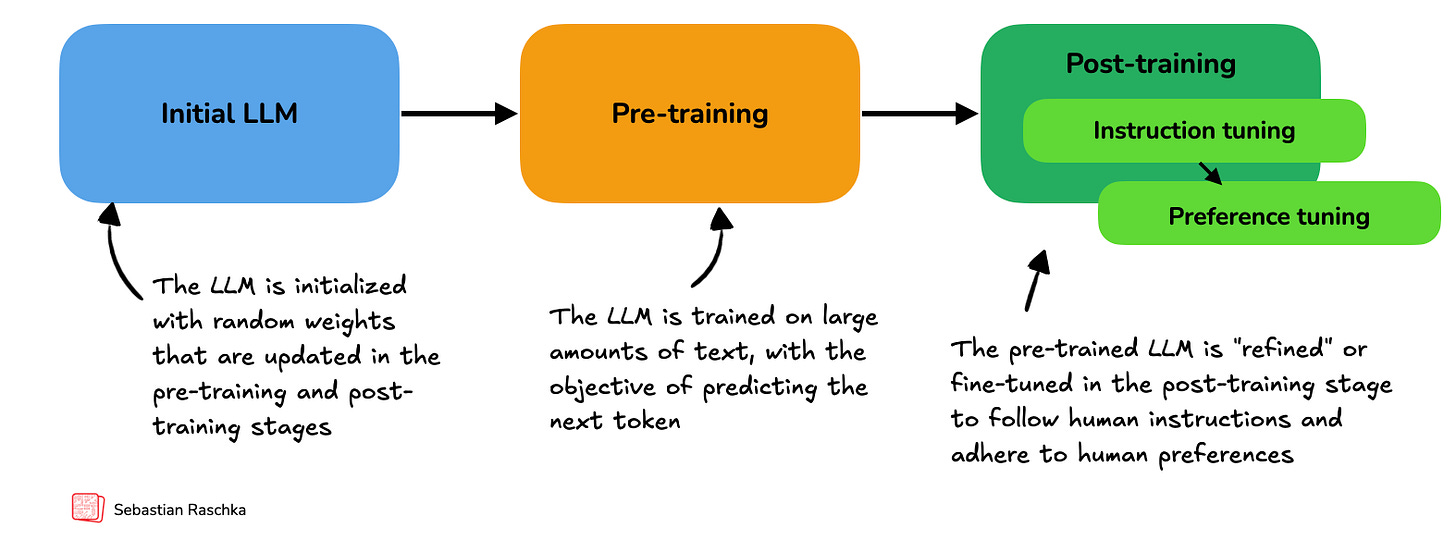

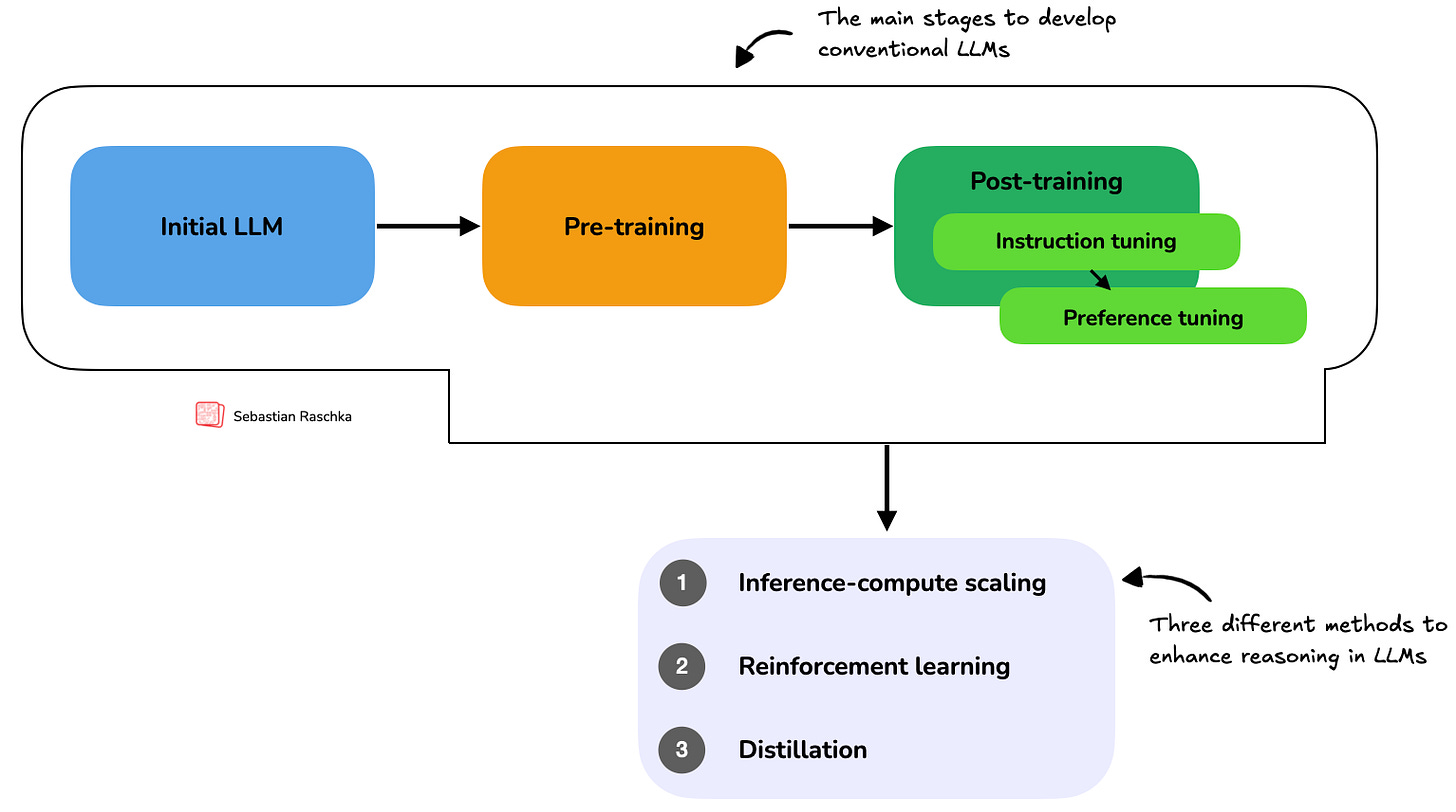

Figure - Caption: Figure 1.2: Overview of a typical LLM training pipeline. The process begins with an initial model initialized with random weights, followed by pre-training on large-scale text data to learn language patterns by predicting the next token. Post-training then refines the model through instruction fine-tuning and preference fine-tuning, which enables the LLM to follow human instructions better and align with human preferences.

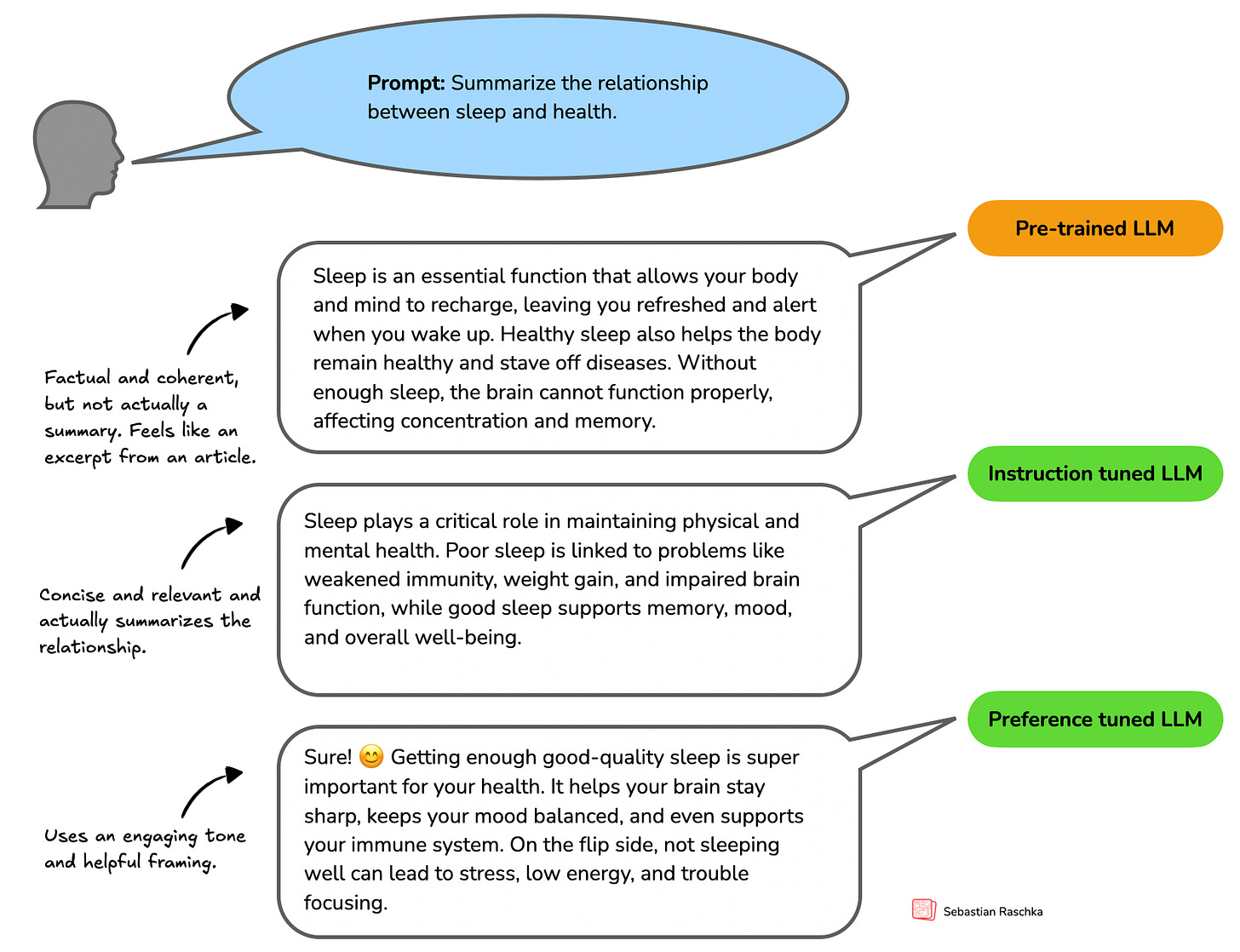

Figure - Caption: Figure 1.3: Example responses from a language model at different training stages. The prompt asks for a summary of the relationship between sleep and health. The pre-trained LLM produces a relevant but unfocused answer without directly following the instructions. The instruction-tuned LLM generates a concise and accurate summary aligned with the prompt. The preference-tuned LLM further improves the response by using a friendly tone and engaging language, which makes the answer more relatable and user-centered.

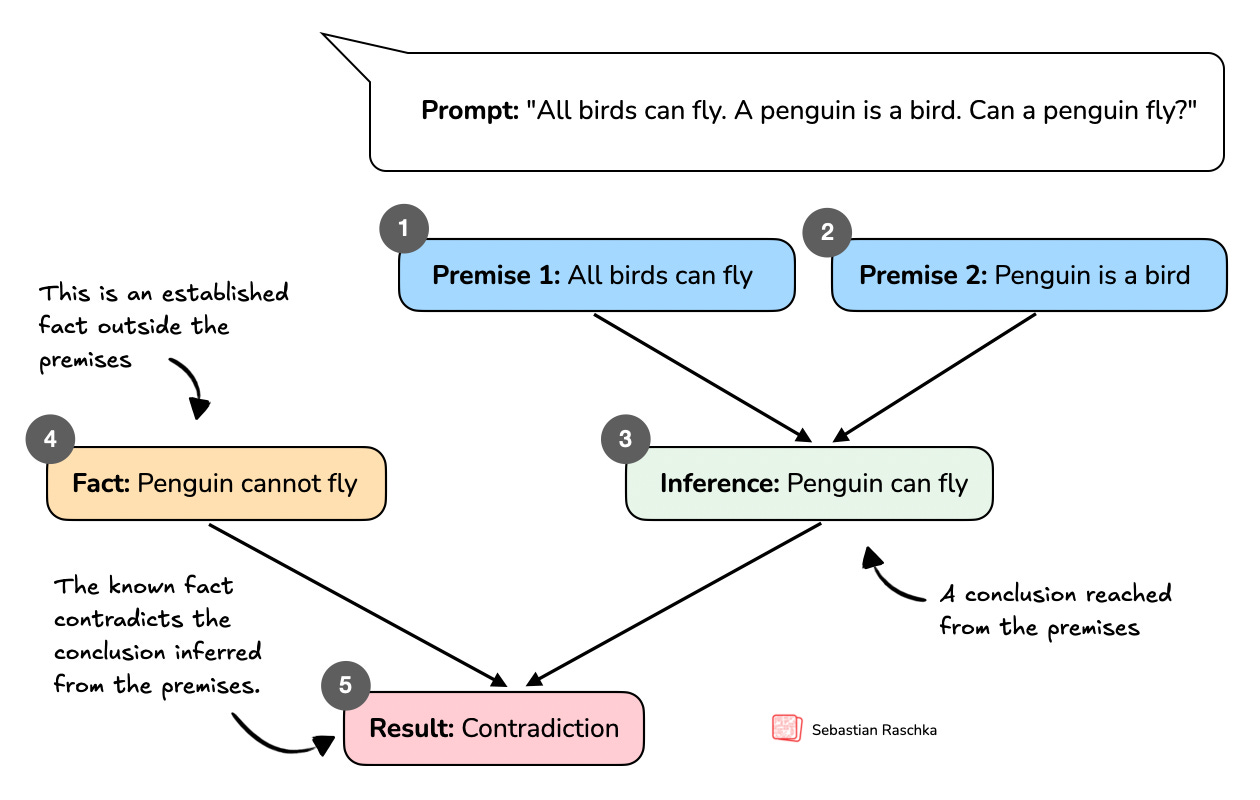

Figure - Caption: Figure 1.4 Illustration of how contradictory premises lead to a logical inconsistency. From “All birds can fly” and “A penguin is a bird,” we infer “Penguin can fly.” This conclusion conflicts with the established fact “Penguin cannot fly,” which results in a contradiction.

Figure - Caption: Figure 1.5: An illustrative example of how a language model (ChatGPT 4o) appears to “reason” about a contradictory premise.

Figure - Caption: Figure 1.6: Three approaches commonly used to improve reasoning capabilities in LLM). These methods (inference-compute scaling, reinforcement learning, and distillation) are typically applied after the conventional training stages (initial model training, pre-training, and post-training with instruction and preference tuning).

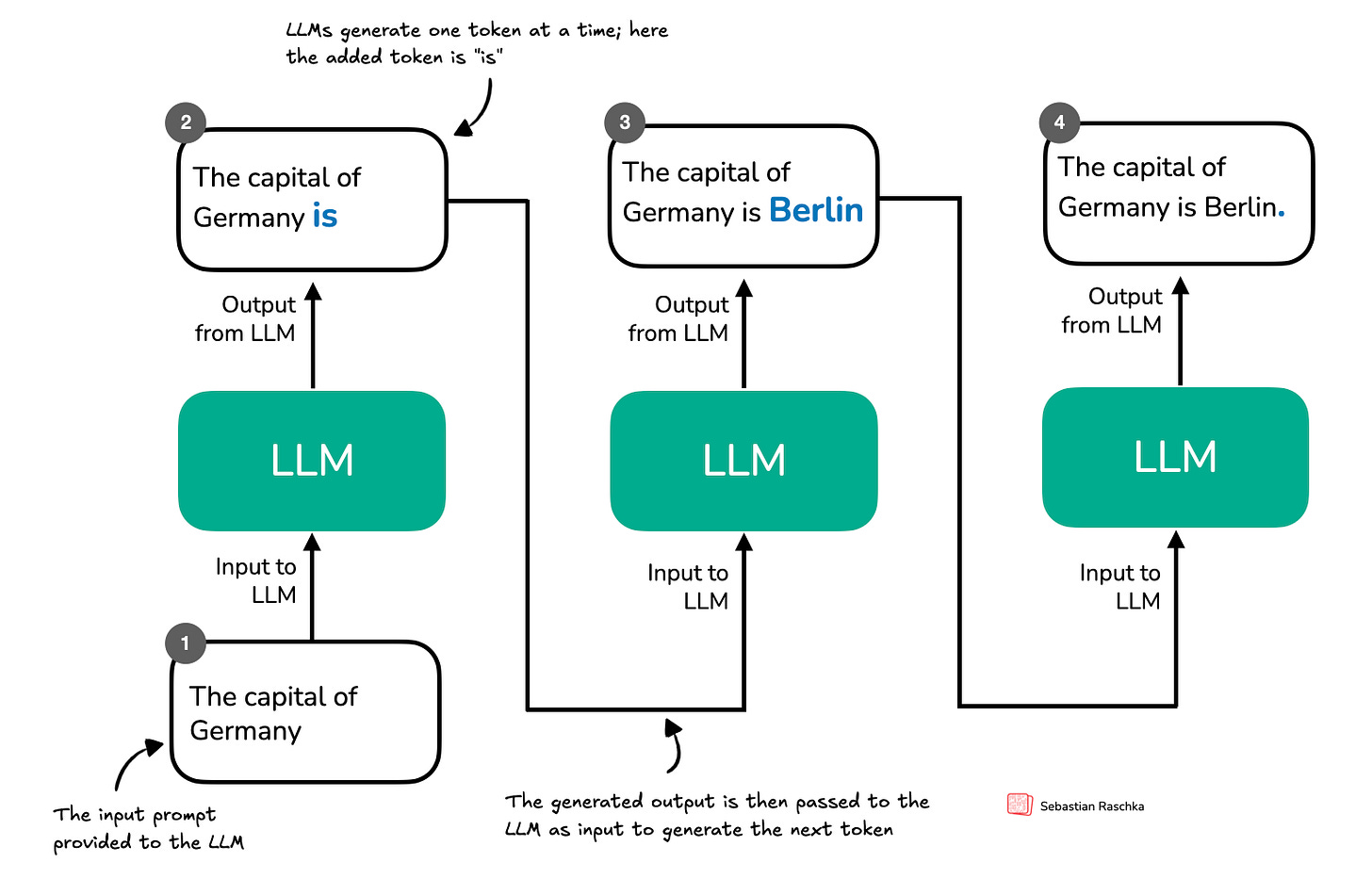

Figure - Caption: Figure 1.7: Token-by-token generation in an LLM. At each step, the LLM takes the full sequence generated so far and predicts the next token, which may represent a word, subword, or punctuation mark depending on the tokenizer. The newly generated token is appended to the sequence and used as input for the next step. This iterative decoding process is used in both standard language models and reasoning-focused models.

Full Text Content

Hi everyone,

As you know, I’ve been writing a lot lately about the latest research on reasoning in LLMs. Before my next research-focused blog post, I wanted to offer something special to my paid subscribers as a thank-you for your ongoing support.

So, I’ve started writing a new book on how reasoning works in LLMs, and here I’m sharing the first Chapter 1 with you. This ~15-page chapter is an introduction reasoning in the context of LLMs and provides an overview of methods like inference-time scaling and reinforcement learning.

Thanks for your support! I hope you enjoy the chapter, and stay tuned for my next blog post on reasoning research!

Happy reading, Sebastian

Chapter 1: Introduction

Welcome to the next stage of large language models (LLMs): reasoning. LLMs have transformed how we process and generate text, but their success has been largely driven by statistical pattern recognition. However, new advances in reasoning methodologies now enable LLMs to tackle more complex tasks, such as solving logical puzzles or multi-step arithmetic. Understanding these methodologies is the central focus of this book.

In this introductory chapter, you will learn:

What “reasoning” means specifically in the context of LLMs.

How reasoning differs fundamentally from pattern matching.

The conventional pre-training and post-training stages of LLMs.

Key approaches to improving reasoning abilities in LLMs.

Why building reasoning models from scratch can improve our understanding of their strengths, limitations, and practical trade-offs.

After building foundational concepts in this chapter, the following chapters shift toward practical, hands-on coding examples to directly implement reasoning techniques for LLMs.

1.1 What Does “Reasoning” Mean for Large Language Models?

What is LLM-based reasoning? The answer and discussion of this question itself would provide enough content to fill a book. However, this would be a different kind of book than this practical, hands-on coding focused book that implements LLM reasoning methods from scratch rather than arguing about reasoning on a conceptual level. Nonetheless, I think it’s important to briefly define what we mean by reasoning in the context of LLMs.

So, before we transition to the coding portions of this book in the upcoming chapters, I want to kick off this book with this section that defines reasoning in the context of LLMs, and how it relates to pattern matching and logical reasoning. This will lay the groundwork for further discussions on how LLMs are currently’ built, how they handle reasoning tasks, and what they are good and not so good at.

This book’s definition of reasoning, in the context of LLMs, goes as follows:

Reasoning, in the context of LLMs, refers to the model’s ability to produce intermediate steps before providing a final answer. This is a process that is often described as chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning. In CoT reasoning, the LLM explicitly generates a structured sequence of statements or computations that illustrate how it arrives at its conclusion.

Figure 1.1 illustrates a simple example of multi-step (CoT) reasoning in an LLM.

Figure 1.1: A simplified illustration of how an LLM might tackle a multi-step reasoning task. Rather than just recalling a fact, the model needs to combine several intermediate reasoning steps to arrive at the correct conclusion. The intermediate reasoning steps may or may not be shown to the user, depending on the implementation.

LLM-produced intermediate reasoning steps, as shown in Figure 1.1, look very much like a person is articulating internal thoughts aloud. Yet how closely these methods (and the resulting reasoning processes) mirror human reasoning remains an open question, one this book does not attempt to answer. It’s not even clear that such a question can be definitively answered.

Instead, this book focuses on explaining and implementing the techniques that improve LLM-based reasoning and make these models better at handling complex tasks. My hope is that by gaining hands-on experience with these methods, you will be better prepared to understand and improve those reasoning methods being developed and maybe even explore how they compare to human reasoning.

Note: Reasoning processes in LLMs may closely resemble human thought, particularly in how intermediate steps are articulated. However, it’s not (yet) clear whether LLM reasoning mirrors human reasoning in terms of internal cognitive processes. Humans often reason by consciously manipulating concepts, intuitively understanding abstract relationships, or generalizing from few examples. In contrast, current LLM reasoning is primarily based on patterns learned from extensive statistical associations present in training data, rather than explicit internal cognitive structures or conscious reflection.

Thus, although the outputs of reasoning-enhanced LLMs can appear human-like, the underlying mechanisms (likely) differ substantially and remain an active area of exploration.

1.2 A Quick Refresher on LLM Training

This section briefly summarizes how LLMs are typically trained so that we can better appreciate their design and understand where their limitations lie. This background will also help frame our upcoming discussions on the differences between pattern matching and logical reasoning.

Before applying any specific reasoning methodology, traditional LLM training is usually structured into two stages: pre-training and post-training, which are illustrated in Figure 1.2 below.

Figure 1.2: Overview of a typical LLM training pipeline. The process begins with an initial model initialized with random weights, followed by pre-training on large-scale text data to learn language patterns by predicting the next token. Post-training then refines the model through instruction fine-tuning and preference fine-tuning, which enables the LLM to follow human instructions better and align with human preferences.

In the pre-training stage, LLMs are trained on massive amounts (many terabytes) of unlabeled text, which includes books, websites, research articles, and many other sources. The pre-training objective for the LLM is to learn to predict the next word (or token) in these texts.

When pre-trained on a massive scale, on terabytes of text, which requires thousands of GPUs running for many months and costs millions of dollars for leading LLMs, the LLMs become very capable. This means they begin to generate text that closely resembles human writing. Also, to some extent, pre-trained LLMs will begin to exhibit so-called emergent properties, which means that they will be able to perform tasks that they were not explicitly trained to do, including translation, code generation, and so on.

However, these pre-trained models merely serve as base models for the post-training stage, which uses two key techniques: supervised fine-tuning (SFT, also known as instruction tuning) and preference tuning to teach LLMs to respond to user queries, which are illustrated in Figure 1.3 below.

Figure 1.3: Example responses from a language model at different training stages. The prompt asks for a summary of the relationship between sleep and health. The pre-trained LLM produces a relevant but unfocused answer without directly following the instructions. The instruction-tuned LLM generates a concise and accurate summary aligned with the prompt. The preference-tuned LLM further improves the response by using a friendly tone and engaging language, which makes the answer more relatable and user-centered.

As shown in Figure 1.3, instruction tuning improves an LLM’s capabilities of personal assistance-like tasks like question-answering, summarizing and translating text, and many more. The preferences tuning stage then refines these capabilities. It helps tailor responses to user preferences. In addition, preference tuning is also used to make LLMs safer. (Some readers may be familiar with terms like Reinforcement Learning Human Feedback or RLHF, which are specific techniques to implement preference tuning.)

In short, we can think of pre-training as “raw language prediction” (via next-token prediction) that gives the LLM some basic properties and capabilities to produce coherent texts. The post-training stage then improves the task understanding of LLMs via instruction tuning and refines the LLM to create answers with preferred stylistic choices via preference tuning.

These pre-training and post-training stages mentioned above are covered in my book “Build A Large Language Model (From Scratch).” The book you are reading now does not require detailed knowledge of these stages. We will start with a model that has undergone pre-training an post-training. Concretely, we implement the architecture of the Initial LLM in Chapter 2 and load openly available weights of a model that has undergone the expensive pre-training and post-training stages mentioned above. After evaluating the base model, the subsequent chapters in this book will then implement and apply reasoning methods on top.

1.3 Pattern Matching: How LLMs Learn from Data

As mentioned in the previous section, during pre-training, LLMs are exposed to vast quantities of text and learn to predict the next token by identifying and reproducing statistical associations in that data. This process enables them to generate fluent and coherent text, but it is fundamentally rooted in surface-level correlations rather than deep understanding.

Most current LLMs like OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4o or Meta AI’s Llama 3, unless explicitly trained or augmented for reasoning, primarily operate in this way. They do not perform explicit, step-by-step reasoning. Instead, they respond to prompts by generating continuations that are statistically consistent with the patterns seen during training. In essence, they match patterns between input and output, rather than deducing answers through logical inference.

Consider the following example:

Prompt: “The capital of Germany is…”

Completion: “Berlin”

An LLM producing the answer “Berlin” is (likely) not logically deducing the answer. Instead, it is recalling a strong statistical association learned from training data. This behavior reflects what we refer to as pattern matching, which means that the model completes text based on learned correlations, not by applying structured reasoning steps.

But what about tasks that go beyond pattern recognition, i.e., tasks where a correct answer depends on drawing conclusions from given facts? This brings us to a different kind of capability: logical reasoning.

Logical reasoning involves systematically deriving conclusions from premises using rules or structured inference. Unlike pattern matching, it depends on intermediate reasoning steps and the ability to recognize contradictions or draw implications based on formal relationships.

For example:

Prompt: “All birds can fly. A penguin is a bird. Can a penguin fly?”

A person, or a system capable of reasoning, would notice that something is off. From the first two facts, you might conclude that a penguin should be able to fly. But if you also know that penguins cannot fly, there is a contradiction, as depicted in Figure 1.4 below. A reasoning system would catch this conflict and recognize that either the first statement is too broad or that penguins are an exception.

Figure 1.4 Illustration of how contradictory premises lead to a logical inconsistency. From “All birds can fly” and “A penguin is a bird,” we infer “Penguin can fly.” This conclusion conflicts with the established fact “Penguin cannot fly,” which results in a contradiction.

In contrast, a statistical (pattern-matching) LLM doesn’t explicitly track contradictions but instead predicts based on learned text distributions. For instance, if “All birds can fly” is reinforced strongly in training data, the model may confidently answer: “Yes, penguins can fly.”

In the next section, we will look at a concrete example of how an LLM handles this “All birds can fly…” prompt.

1.4 Simulated Logical Reasoning: How LLMs Mimic Logic without Explicit Rules

In the previous section, we saw how contradictory premises can lead to logical inconsistencies. A conventional LLM does not explicitly track contradictions but generates responses based on learned text distributions.

Let’s see a concrete example, shown in Figure 1.5, of how a non-reasoning-enhanced LLM like OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4o responds to the “All birds can fly…” prompt discussed in the previous section.

Figure 1.5: An illustrative example of how a language model (ChatGPT 4o) appears to “reason” about a contradictory premise.

The example in Figure 1.5 shows that ChatGPT 4o appears to answer correctly even though ChatGPT 4o is not considered a reasoning model, unlike OpenAI’s other offerings like ChatGPT o1 and o3, which have been explicitly developed with reasoning methodology.

So, how did this happen? Does this mean ChatGPT 4o explicitly reasons logically? No, not necessarily. However, at least 4o is highly effective at simulating logical reasoning in familiar contexts.

ChatGPT 4o does not implement explicit contradiction-checking and instead generates answers based on probability-weighted patterns. This approach works well enough if training data includes many instances correcting the contradiction (e.g., text like “penguins cannot fly”) so that the model learns a statistical association between “penguins” and “not flying.” As we see in Figure 1.5, this allows the model to answer correctly without explicitly implementing rule-based or explicit logical reasoning methodologies.

In other words, the model recognizes the contradiction implicitly because it has frequently encountered this exact reasoning scenario during training. This effectiveness relies heavily on statistical associations built from abundant exposure to reasoning-like patterns in training data.

So, even when a conventional LLM seems to perform logical deduction as shown in Figure 1.5, it’s not executing explicit, rule-based logic but is instead leveraging patterns from its vast training data.

Nonetheless, ChatGPT 4o’s success here is a great illustration of how powerful implicit pattern matching can become when trained at a massive scale. However, these types of pattern-based reasoning models usually struggle in scenarios where:

The logical scenario is novel (not previously encountered in training data).

Reasoning complexity is high, involving intricate, multi-step logical relationships.

Structured reasoning is required, and no direct prior exposure to similar reasoning patterns exists in training data.

Note: Why are explicit rule-based systems not more popular? Rule-based systems were used widely in the ’80s and ’90s for medical diagnosis, legal decisions, and engineering. They are still used in critical domains (medicine, law, aerospace), which often require explicit inference and transparent decision processes. However, they are hard to implement as they largely rely on human-crafted heuristics. However, deep neural networks (like LLMs) prove to be great and flexible at many tasks when trained at scale.

We might say that LLMs simulate logical reasoning through learned patterns, and we can improve it further with specific reasoning methods that include inference-compute scaling and post-training strategies, but they’re not explicitly executing any rule-based logic internally.

Moreover, it’s worth mentioning that reasoning in LLMs exists on a spectrum. Even before the advent of ChatGPT o1 and DeepSeek-R1, LLMs were capable of simulating reasoning behavior, that is, exhibiting behaviors aligning with our earlier definition, such as generating intermediate steps to arrive at correct conclusions. What we now explicitly label a “reasoning model” is essentially a more refined version of this capability. This is achieved by leveraging specific inference-compute scaling techniques and targeted post-training methods designed to improve and reinforce this behavior.

The rest of this book focuses specifically on these advanced methods that improve LLMs to solve complex problems, helping you better understand how to improve the implicit reasoning capabilities in LLMs.

1.5 Improving Reasoning in LLMs

Reasoning in the context of LLMs became popular in the public eye with the announcement of OpenAI’s ChatGPT o1 on September 12, 2024. In the announcement article, OpenAI mentioned that

We’ve developed a new series of AI models designed to spend more time thinking before they respond.

Furthermore, OpenAI wrote:

These enhanced reasoning capabilities may be particularly useful if you’re tackling complex problems in science, coding, math, and similar fields.

While the details of ChatGPT o1 are not publicly available, the common perception is that the o1 model is based on one of the predecessors, like GPT-4, but uses extensive inference-compute scaling (more on that later) to achieve these enhanced reasoning capabilities.

A few months later, in January 2025, DeepSeek released the DeepSeek-R1 model and technical report, which details training methodologies to develop reasoning models, which made big waves as they not only made freely and openly available a model that competes with and exceeds the performance of the proprietary o1 model but also shared a blueprint on how to develop such model.

This book aims to explain how these methodologies used to develop reasoning models work by implementing these methods from scratch.

The different approaches to developing and improving an LLM’s reasoning capabilities can be grouped into three broad categories, as illustrated in Figure 1.6 below.

Figure 1.6: Three approaches commonly used to improve reasoning capabilities in LLM). These methods (inference-compute scaling, reinforcement learning, and distillation) are typically applied after the conventional training stages (initial model training, pre-training, and post-training with instruction and preference tuning).

As illustrated in Figure 1.6, these methods are applied to LLMs that have undergone the conventional pre-training and post-training phases, including instruction and preference tuning.

- Inference-time compute scaling

Inference-time compute scaling (also often called inference compute scaling, test-time scaling, or other variations) includes methods that improve model reasoning capabilities at inference time (when a user prompts the model) without training or modifying the underlying model weights. The core idea is to trade off increased computational resources for improved performance, which helps make even fixed models more capable through techniques such as chain-of-thought reasoning, and various sampling procedures.

This topic will be the focus of Chapter 4.

- Reinforcement learning

Reinforcement learning (RL) refers to training methods that improve a model’s reasoning capabilities by encouraging it to take actions that lead to high reward signals. These rewards can be broad, such as task success or heuristic scores, or they can be narrowly defined and verifiable, such as correct answers in math problems or coding tasks.

Unlike scaling compute at inference time, which can improve reasoning performance without modifying the model, RL updates the model’s weights during training. This enables the model to learn and refine reasoning strategies through trial and error, based on the feedback it receives from the environment.

We will explore RL in more detail in Chapter 5.

Note: In the context of developing reasoning models, it is important to distinguish the pure RL approach here from reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) used during preference tuning when developing a conventional LLM as illustrated previously in Figure 1.2. RLHF incorporates explicit human evaluations or rankings of model outputs as reward signals, directly guiding the model toward human-preferred behaviors. In contrast, pure RL in the context of reasoning models typically relies on automated or environment-based reward signals, which can be more objective but potentially less aligned with human preferences. For instance, pure RL might train a model to excel at mathematical proofs by providing explicit rewards for correctness. In contrast, RLHF would involve human evaluators ranking various responses to encourage outputs that align closely with human standards and subjective preferences.

- Supervised fine-tuning and model distillation

Distillation involves transferring complex reasoning patterns learned by powerful, larger models into smaller or more efficient models. Within the context of LLMs, this typically means performing supervised fine-tuning (SFT) using high-quality labeled instruction datasets generated by a larger, more capable model. This technique is commonly referred to as knowledge distillation or simply distillation in LLM literature. However, it’s important to note that this differs slightly from traditional knowledge distillation in deep learning, where a smaller (“student”) model typically learns from both the outputs and the logits produced by a larger (“teacher”) model.

This topic is discussed further in Chapter 6.

Note: The SFT technique here is similar to the SFT technique used when developing a conventional LLM, except that the training examples are derived from a model explicitly developed for reasoning. Consequently, the training examples here focus more on reasoning tasks and typically include intermediate reasoning steps.

1.6 The Importance of Building Reasoning Models From Scratch

Following the release of DeepSeek-R1 in January 2025, improving the reasoning abilities of LLMs has become one of the hottest topics in AI, and for good reason. Stronger reasoning skills allow LLMs to tackle more complex problems, making them more capable across various tasks users care about.

This shift is also reflected in a February 12, 2025, statement from OpenAI’s CEO:

We will next ship GPT-4.5, the model we called Orion internally, as our last non-chain-of-thought model. After that, a top goal for us is to unify o-series models and GPT-series models by creating systems that can use all our tools, know when to think for a long time or not, and generally be useful for a very wide range of tasks.

The quote above underlines the major shift from leading LLM providers towards reasoning models, where “chain-of-thought” refers to a prompting technique that guides language models to reason step-by-step to improve their reasoning capabilities, which we will cover in more detail in Chapter 4.

Also noteworthy is the mention of knowing “when to think for a long time or not.” This hints at an important design consideration: reasoning is not always necessary or desirable.

For instance, reasoning models are designed to be good at complex tasks such as solving puzzles, advanced math problems, and challenging coding tasks. However, they are not necessary for simpler tasks like summarization, translation, or knowledge-based question answering. In fact, using reasoning models for everything can be inefficient and expensive. For instance, reasoning models are typically more expensive to use, more verbose, and sometimes more prone to errors due to “overthinking.” Also, here, the simple rule applies: Use the right tool (or type of LLM) for the task.

Why are reasoning models more expensive than non-reasoning models? Primarily because they tend to produce longer outputs, due to the intermediate reasoning steps that explain how an answer is derived. As illustrated in Figure 1.7, LLMs generate text one token at a time. Each new token requires a full forward pass through the model. So, if a reasoning model produces an answer that is twice as long as that of a non-reasoning model, it will require twice as many generation steps, resulting in twice the computational cost. This also directly impacts cost in API usage, where billing is often based on the number of tokens processed and generated.

Figure 1.7: Token-by-token generation in an LLM. At each step, the LLM takes the full sequence generated so far and predicts the next token, which may represent a word, subword, or punctuation mark depending on the tokenizer. The newly generated token is appended to the sequence and used as input for the next step. This iterative decoding process is used in both standard language models and reasoning-focused models.

This directly highlights the importance of implementing LLMs and reasoning methods from scratch. It’s one of the best ways to understand how they work. And if we understand how LLMs and these reasoning models work, we can better understand these trade-offs.

1.7 Summary

Reasoning in LLMs) involves systematically solving multi-step tasks using intermediate steps (chain-of-thought).

Conventional LLM training occurs in several stages:

Pre-training, where the model learns language patterns from vast amounts of text.

Instruction tuning, which improves the model’s responses to user prompts.

Preference tuning, which aligns model outputs with human preferences.

Pattern matching in LLMs relies purely on statistical associations learned from data, which enables fluent text generation but lacks explicit logical inference.

Improving reasoning in LLMs can be achieved through:

Inference-time compute scaling, enhancing reasoning without retraining (e.g., chain-of-thought prompting).

Reinforcement learning, training models explicitly with reward signals.

Supervised fine-tuning and distillation, using examples from stronger reasoning models.

Building reasoning models from scratch provides practical insights into LLM capabilities, limitations, and computational trade-offs.

After introducing the concepts and motivations behind reasoning in LLMs, the coming chapters will be more hands-on, where we will begin implementing reasoning-improving techniques from scratch.

References and Further Reading

References

Introducing OpenAI o1-preview: Overview of the o1 release by OpenAI.

DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning: A research paper exploring reinforcement learning techniques to improve LLM reasoning.

OpenAI CEO’s comment on the reasoning capabilities of future models: A brief statement by OpenAI’s CEO on upcoming model releases in context with reasoning capabilities.

Build a Large Language Model (From Scratch): An in-depth guide on implementing and training large language models step-by-step.

Further Reading

Understanding Reasoning LLMs: An introduction to how DeepSeek-R1 works, providing insights into the foundations of reasoning in LLMs.